|

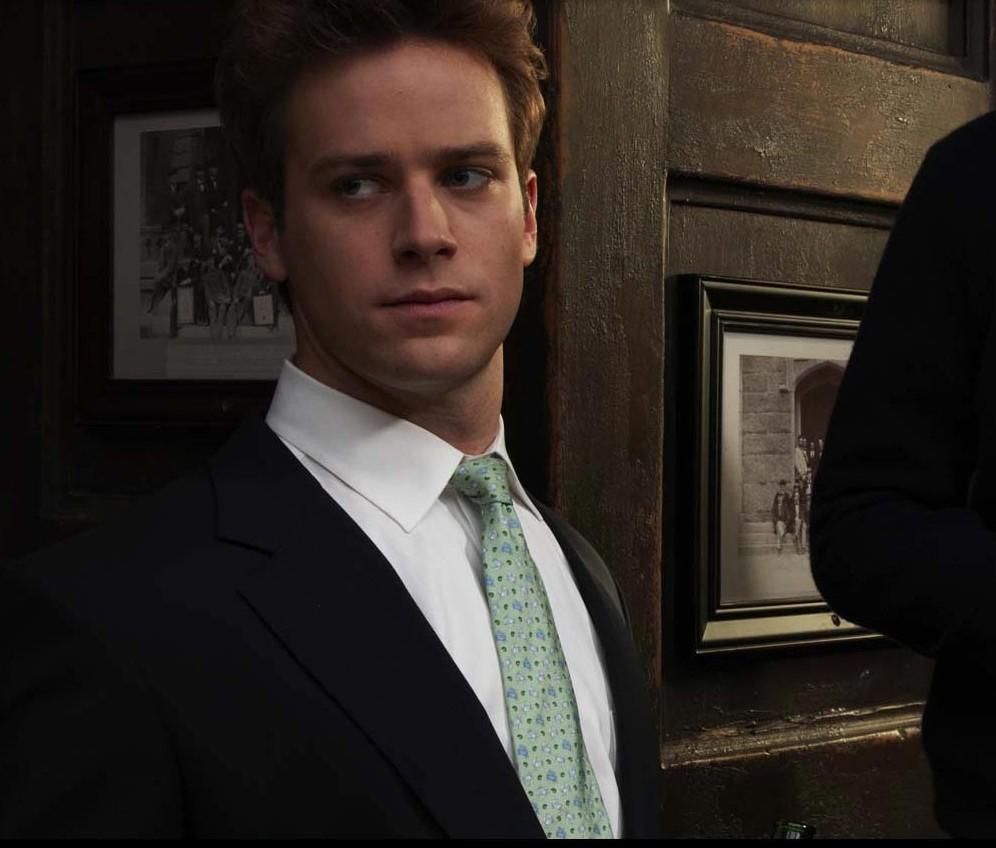

| Tyler Coleridge |

"But they are my flock - I must see to their blessed lives, not murder them." Coleridge could understand why death wanted souls, but it did not mean that Coleridge would walk them to his gaping maw.

"You forget yourself, my son," said Hades, face covered in a helm of twisted skulls. He was robed in darkness. "I do not ask this of you - I demand it." Hades was less pronounced in the dream state. Had Coleridge seen the God of Death in person, he would not have been able to resist his father's demand. "When you wake, there will be a list of names - see to their passing as I have instructed."

Coleridge had no choice. When he woke, he saw the list of names written in his own hand. There were thirty-six listed. The entire Marshal family was present, aside from two children, and most of the upper class and affluent citizens in King's County.

The first time he killed had been so sudden, and he had been scared - worried he'd get captured. He invited the elder Marshal to his home for dinner - an introductory ruse utilized to put his victim at ease - and applied a poison that rendered the elder Marshal unconscious for a few hours, as well as paralyzed for half a day. Hades called the poison Anthoss Thanatoo, and had instructed Coleridge to speak the phrase over the concoction to make the poison effective. It seemed similar to the transubstantiation that took place during the Christian ritual of Mass - where the wine and bread became the blood and body of Christ.

The poison worked, and Coleridge took his victim to the basement altar. He cut each limb from the elder Marshal's body, and buried them at each cardinal direction outside the church. The right arm was buried east; the left was buried west; the left leg was buried south; the right leg was buried north. The body was taken to the church cemetery, where Coleridge cremated it in a ceremony Hades interpreted as "Cleansing the Soul." It made the person fit for Hades' realm.

It had taken him six years to get the names on the list completed - to find the perfect time for their deaths and to exact Hades' will. After the first twelve names, Coleridge began enjoying how much power he held over his victims. The last and final victim, Jeffrey Donaldson - a banker from Manhattan who moved to Long Island for status and recognition - actually awoke just before Coleridge began his work. He had wanted to savor Donaldson's murder. The banker had been hedonistic in his life - drinking, whoring around, gambling, stealing money - Donaldson had confessed to it all during a proud drunken boast just before Coleridge invited him to dinner.

|

| Jeffrey Donaldson |

"What are you doing, Bishop?" asked the tied and bound Donaldson, a fearful look on his stern boyish face. Coleridge had a chopping blade in his right hand and a hand-saw in his left. "Where are we?"

"What do you think I'm going to do, Jeffrey?" asked Coleridge with a smile twisting his lips.

"If it's money you want, I can get it for you - name your price," pleaded Donaldson. Coleridge could feel the fear in Donaldson's eyes. The man was trying to stay calm, but the confusion gripping his heart was playing games with his imagination. Coleridge could sense every ounce of panic that dripped from Donaldson's words.

"The Church has plenty, Jeffrey."

"You want some women - I won't say anything."

"I have taken a vow that I hold dear."

"I can get you more land - more land will help you house the homeless, right? You want a house?" Coleridge smiled at Donaldson's grasping attempts to placate him. The Child of Hades could only be placated by one gift.

"I do want something you can give me, Jeffrey."

"Anything - you name it." The brief appearance of relief was all that Coleridge wanted to see on his last victim. He savored Donaldson's illusion of hope for an extended moment of succulence. He sighed, then went on.

"Your soul, Jeffrey. You can give me your soul." Coleridge smiled. The sudden horrified shock in Donaldson's pallor made Coleridge laugh. He loved seeing his victim's hope evaporate.

Coleridge raised his knife and hacked into Donaldson's upper arm, licking the splash of blood that hit near his mouth. He opened the gash in the man's bicep to reveal the place he would begin working with the hand-saw. Donaldson screamed in pain, terror dripping from his cry. He began calling for help.

"No one is here to hear you, Jeffrey," said Coleridge as he lined up the saw. "But you may call out all you like." Coleridge moved the saw back and forth against the rough muscle and then through the bone. The smell of raw bone made Coleridge's nerves tingle with delight. He drank in every cry Donaldson gave. The screams began low, and then raised to a feverish pitch before Donaldson passed out from the pain. The blood spurted everywhere. Coleridge was covered. He didn't mind; he enjoyed his work.

The rest of the kill went as planned - each limb buried in place, and the torso and head placed on a pyre for cremation. Coleridge tied Donaldson to the platform of sticks and dried logs. Donaldson woke one last time. He began crying after realizing what was to become of him. Donaldson had finally given up, seeing his arms and legs gone.

"Crying for your loss, Jeffrey?" asked Coleridge as he finished the bindings.

"You're going to rot in hell for this," declared Donaldson. His voice spit vitriol. Coleridge was surprised the man could still voice words after the amount of blood that was lost on the altar.

"I will sit by my father's side for this, Jeffrey."

"You think you'll be going to heaven? You'll be in hell, right beside me!" Donaldson must have thought it would phase Coleridge.

"I will be in hell, yes, but at my father's side - not yours." Donaldson's eyes widened, his tears ceased. That familiar look of fright dressed his face. Coleridge drank the last sip he could, and lit the pyre. He spoke the chanting words of the ceremony. The screams of Donaldson as he burned were a chorus of praise to his father. Hades would be proud of him, that night - as he finished his first list.

He had to make his exit the next morning. A crowd of people were worried about the sounds they heard echoing from the Cathedral the night before. Coleridge had tried to assuage their fears, but the crowd was insistent. They marched in and to the back, where Coleridge's bloody ceremonial robes were still out. He had yet to burn them, as well. They found them and began accusing him of the murder of Donaldson - who told everyone that he was having dinner with the Bishop the previous evening.

Coleridge took a horse from the church's stables, and made his retreat to the ferry. Just as the ferryman left the dock, Coleridge saw the torch-bearing crowd of people descending upon the landing. He was just in time to avoid them. He passed it off as a farewell ceremony so the ferryman wouldn't take him back to face the mob. That night, he slept in the cold northern night under a tree. The blanket under the saddle was the only warmth offered to him. He had only had enough time to gather a small amount of money from the church coffers before he fled.

He dreamed of his father for the first time since 1857.

"You have done well, son," said the figure of Hades, still garbed in the mask of skulls. "But now, you're calling lies west of here."

"Where must I go, Divine Father?"

"The City on the Lake," Coleridge was given an image that could only have been Chicago, from the stories he'd been told and the sketches he'd seen. "There you will find your way towards the chosen fate."

It was a short dream, but one he did not forget. It took him a week and a half to get there by horse. He could have taken a train, but he did not want to be noticed. When he reached the shores of the Great Lake Michigan, and saw the City on the Lake his father had shown him, he grinned from ear to ear in satisfied accomplishment. He decided he would sleep the night on the windy shore, and then go into the burgeoning city the next morning. He dreamed of hell once more, and woke with a new list, written in his own hand-writing. It contained twelve names.

Coleridge did not know who those names were, or what Chicago had in store for him, but he did know it was going to be a busy summer.

.jpg)